November 2, 2019

Tomas' Pumpkins, 2019

Click on any image for a full screen view.

In 2017, I posted a Blog Entry on Tomas' Pumpkins, an annual project of Tomas Gonzalez of Washington. NJ. For some background on Tomas (The "Picasso of Pumpkins") and his work, as well as photos of the 2017 crop. This year I went back again to document the 2019 collection. There are links to other years' collections at the bottom of this post.

Tomas' Pumpkins, 2019

Click on any image for a full-screen version.

All of these carved pumpkins are works of Tomas Gonzales of Washington, New Jersey.

This is an ongoing multi-year collection.

Designs for these pumpkins are Registered Copyright ©T.Gonzales

Tomas may be reached at: gonzales.tomas1@gmail.com

To see photos of other years' displays, click here.

Photo 10, "the Bridge", can give only the faintest inkling of the magical setting of the display, and the surroundings. It's a rural one-lane bridge across a stream that borders his property on a dead end road. On the Saturday night after Halloween, it becomes the site of a neighborhood gathering with a bonfire in the back yard, over which simmers a cauldron of chile. And locals and friends gather in the chill air of a new winter. The faint gurgle of the water mingles with the quiet indistinct conversations of the congregation, and there is an atmosphere of peace and gaity and companionship that pervades the scene. It's a good place to be.

October 5, 2019

Home Improvement Gone Off the Rails

Click on any image for a full screen view.

If I ever sell my house, I'm probably going to have to write a service manual, and maybe even provide a service contract. I've done so many Rube-Goldberg improvements, modifications, and innovations to the various systems, that no plumber is going to be able to figure out what all those extra pipes and valves are for on my heating system or what that funny looking control box is on my window sill, or any of that stuff.

Take, for example, my wood stove. My home is subject to flooding from the Rockaway River that borders my back yard. Except when it borders my front yard. I took care of that problem back in 1980 after the first time the house got flooded. I raised the house one full storey, turning what once was a crawlspace into a full height garage under the house. The house has not had water in it since. See my Blog entry for March 11, 2011, God Willin' an' the Crick Don't Rise.

One of the impediments to raising the house was the rustic fieldstone chimney, which could not be lifted up with the rest of the house. I had to dismantle the chimney rock by rock before raising the wooden structure, and then build it back up again, adding more rocks gleaned from around the neighborhood, to raise the chimney to the increased height.. I performed those tasks entirely by myself, with minimal instruction from a stonemason as follows:

ME: "What's that stuff you put in between the rocks?"

MASON: "You mix one part Portland cement to three parts sand, and then add enough water so that it feels right."

ME: "OK. Thanks."

You can observe my progress as a stonemason by examining the chimney. The stonework gets neater the higher you look. And it hasn't fallen over in 40 years, and the smoke still goes up the chimney instead of into the living room, so I got the main gist of the job right.

When I rebuilt the chimney, I decided to install a woodstove in the new fireplace to get some efficient heat out of the hearth, replacing the original, mostly decorative fireplace. And I figured, as long as I was going to be building the chimney around the stove, I might as well employ a trick I had heard about somewhere to improve the stove's efficiency still further. I got a stove made of steel, rather than cast iron, because steel can be welded. And I had a metalworker weld a length of 4" pipe into the back of the stove that would run through the stonework to the outside to serve as the air intake for the fire. The theory is that with a normal woodstove, the fire uses air from inside the house to burn the wood. And that draws cold air from the outside in through gaps in the structure, chilling the room air. But if you burn the wood with outside air, that won't happen.

I also designed and installed a forced hot air system to distribute the heat from the stove throughout the house. But that will be the subject of a future Blog post.

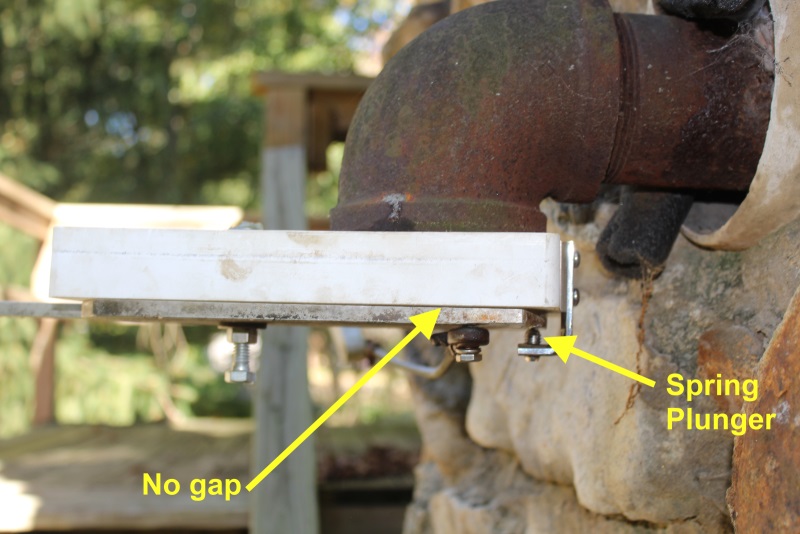

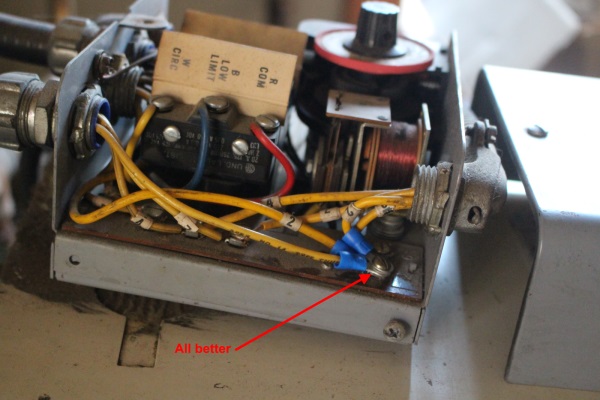

The stove had no damper on the flue to regulate the flame. Instead, it was equipped with a sliding grate to shut down the intake air by degrees. I had to seal up that grate, and install an equivalent mechanism on the outside end of the new air intake pipe to regulate the flow of oxygen to the flame. So I cobbled up the damper valve shown in Photos 3 and 4 from scrap material lying around the machine shop at work. It's a piece of plastic that bolts onto an elbow at the end of the air intake pipe. It has a big hole the size of the pipe to let the air in, and flat aluminum plate that can be rotated to cover the hole (Photo 3) or uncover it (Photo 4). In order to adjust the damper valve from inside the house, there's an operating pushrod attached to the plate at one end, and a lever on the other end. That lever is rotated by a shaft that passes through a length of half-inch pipe going through the stonework of the chimney. The pipe has bearings at both ends which support the shaft. Inside the house, there's another lever at the other end of the shaft, shown within the red circle on Photo 2. So by rotating the inside lever, I can open or close the air intake, thereby regulating the flame. I installed both the 4 inch pipe and the half inch pipe in the process of rebuilding the chimney, and built the stonework around the pipes.

That all worked very nicely except for one minor nagging problem. There was play between the pivot shaft and the plastic body of the valve, which allowed the aluminum plate to sag a little bit, causing a substantial gap between the aluminum and the plastic (Photo 5). So I couldn't fully close off the intake, which limited how low I could damp down the flame. So if the outside temperature was above around 40°, the house would get too warm when the stove was burning, and I'd have to shut down the stove and use the main oil burning heating system of the house.

I lived with that situation for almost 40 years. It wasn't a big problem. But it always bugged me at the back of my mind. So this past summer, I had some time on my hands, so I thought I'd tackle the problem as a project. It wasn't too difficult to solve in concept. There is a commercial device called a "spring plunger". It's sort of like a setscrew with a small spring-loaded rod sticking out one end. The exposed end of the rod is rounded off. All I needed to do would be to rig up a bracket attached to the plastic piece that would mount one of these spring plungers so that it pushed upwards against the aluminum plate, forcing it up against the bottom surface of the plastic, thereby closing the gap. So I designed up the new parts, and made drawings of the existing parts describing what modifications needed to be made to accommodate the new parts. But now I was faced with one big difficulty: Making and modifying the various parts.

I had made all the parts for the original valve assembly at work. Until I retired, I was a machine design engineer. And every place I worked for had a well equipped machine shop with lathes and milling machines and drill presses and band saws and sheet metal brakes; everything I needed to make specialized parts out of metal and plastic. And I've sorely missed access to such equipment since I retired. I might have even bought my own equipment if I had a place to set it up. But the only spare place I have available would be my garage, which floods on a regular basis. I can move my car to avoid the water. I can't move an 800 pound pound milling machine. I was going to have to farm the job out. I looked at various "maker spaces", the latest go-to solution for do-it-yourselfers. But while the ones I found were well equipped with all sorts of trendy 3-D printers, and looms, and ceramic kilns, and woodworking equipment for hobbyists, not a one of them had so much as a drill press for old fashioned manufacturing. I was going to have to find a commercial machine shop to farm out the job.

And here's where the whole project took a left turn into the Twilight Zone.

I googled "Machine shops near me". The first one on the list was 3 miles from my house. Which puzzled me, because my town is almost 100% residential. There's not so much as a supermarket, let alone any heavy industry. But I gave them a call. I got the usual phone menu. But any choice I made on the phone menu, led to endless Muzak and no opportunity speak with a human, or even to leave a voicemail message. So, I figured, it's only three miles. I'll take a ride down there and knock on their door. I put my parts to be altered and drawings in a shopping bag, entered the address of the shop into my car's GPS, and set off, wondering where it would lead me.

And when the nice lady who lives in my dashboard announced, "You have arrived!" it dawned on me. Oh! the ARC facility!

Aircraft Radio Corporation is a little piece of aviation history right in my home town of Boonton Township, NJ. It was a principal pioneer and major manufacturer of avionics for military, commercial, and, general (private) aircraft from the 1920s to the 1950s. It is a sprawling facility incorporating many low manufacturing buildings, warehouses, and laboratories, and a grass airstrip that was still operational when I first moved into my house. It is the site where, in the early 30s, pioneer aviator Jimmy Doolittle teamed with ARC to accomplish the world's first "blind" landing in biplane with an opaque hood over the cockpit. That was the first milestone in developing today's all-weather instrument flight technology. ARC had developed the radio-beam and onboard radio receiver navigation equipment essential to the flight. I had passed the entrance every day on my commute when I was working, but had never looked into it.

I turned in the driveway, and started poking around, and it started to get weird. The place had the dystopian look of an abandoned industrial park after the apocalypse. Buildings were in various states of abandonment, disuse, and disrepair with grass growing in the parking lots, and interior roads with just enough pavement to have potholes. The airstrip had been converted to athletic fields. One of the buildings had been re-purposed as a Korean Catholic Church. I finally found a building that showed some signs of occupancy, and went up and pounded on the locked door. A man came out, and answered my query about the machine shop with a set of complicated directions that would take me to the farthest corner of the facility. I followed his directions along the abandoned roads until I came to a parking lot that actually contained a few cars, and a building with the machine shop's name on it.

|

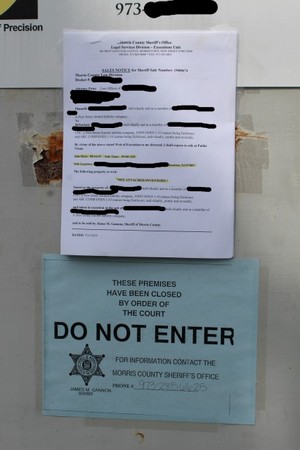

I walked up to the main entrance, and was presented with a couple of uninviting signs (Photo 6). I tried the door. Locked. I knocked. No response. Oh, well. I headed back to the car and was just about to drive away when I noticed another door to a lower level off to the side (Photo 8). I walked up and saw that the lock plate had been pried away from the door (Photo 9).

Oooooo-kay.

I walked up to the door and pulled on the handle. It resisted some, but a sharp tug broke it free, and the door opened. By all rights, it should have creaked ominously, but it didn't. There was a set of steps leading down to another locked door with another "Beware of the Dog" sign. With heart pounding, I hesitantly rapped on the door.

And there appeared a friendly fellow, who opened the door, greeted me, and asked me how he might help me. I explained my situation, showed him the drawings and parts, and asked if he could do the job. He looked at my materials, and said, sure. No problem. He showed me around his facility, which was chock full of a lot of high-end equipment for CNC machining, laser cutting, and other fancy stuff. But there were also a simple Bridgeport milling machine, a metal lathe, and other manually operated machines, more suitable to my little project. He even offered to let me use the equipment myself as long as I signed a waiver absolving him of any responsibility should I cut off a finger or two. I was delighted. Not only had I found someone to do the job, but solved my problem of not having access to a machine shop for personal projects in the future. I was tempted to take a whack at the job myself. But I'm a better engineer than I am a machinist. And I figured I'd leave this one to a pro. I left the parts and drawings with him to work up a quote. He emailed me back a reasonable price, and we agreed to let him squeeze the job in between his production runs when he had a space. This was in June, and I wouldn't be needing heat in the house for several months yet.

A month and a little more went by, and I heard nothing from him. So towards the end of July, I called to see if there had been any progress. Again I got the Muzak and no answer. Emails I sent produced a similar lack of response. So at the beginning of August, I figured I had better find out what was happening. I drove down to his shop, and found the following interesting notice taped onto the lower level entrance:

Well, that was a revoltin' development! The whole damper mechanism was somewhere in the facility, and neither I nor the owner had access to them. And when the building contents were auctioned off, whoever purchased them would find my parts. And not knowing what they were or having any use for them himself, he would toss them in the dumpster. And I'd have no means of regulating my woodstove.

I called the phone number on the Sheriff's Notice, and explained my dilemma to the nice lady who answered. She explained to me that the seizure was the outcome of a lawsuit against the owner of the machine shop. He owed money to the plaintiff, and the judgement was that the property would be auctioned off to raise the money to pay off the debt. She gave me the name of the judge in the case, and suggested I go to the County Building in Morristown, and speak to him.

I did that, and spent several hours being shunted from one office to another. I never did get to talk to the judge, but at least I got some official documents about the lawsuit, giving names and contact information of the Plaintiff, and the Defendant, and their respective lawyers. Reading the papers, I discovered that the Plaintiff was another machine shop.

At the same address!

In an adjacent building on the ARC facility!!

I called both litigants and both lawyers. The Defendant's phone number still only gave me Muzak. But I did get to speak with the Plaintiff and both lawyers. All of them listened to my plight with some sympathy, but were cautiously closed-mouthed about how or if I might retrieve my parts and drawings. In the end, I was recommended to show up at the auction, and speak to the various parties before it took place.

The auction was to take place on August 16 in the parking lot that served both machine shops. I was the first to arrive. And shortly thereafter appeared a clown-car full of characters. There were 6 uniformed Sheriff's Deputies, one town cop, the Plaintiff, the Defendant, and both lawyers. And this being the Crime of the Century in Boonton Township, everyone wanted to be in on the action. I wondered where the mayor was. I finally got to talk to the Defendant, as well as the Plaintiff and the lawyers. And they all continued to be stubbornly noncommittal about how to resolve my issue. They all huddled together with the Deputies and the cop. And it was finally resolved that I was to be escorted into the building with the two litigants, and a Deputy. The Defendant located my stuff in his office and gave it to me, with everyone witnessing that I didn't walk out of the place with a CNC milling machine stashed away in my breast pocket.

OK. I now had my parts back. But I was back to square one on how to get the machine work done. Well, I now knew where I could find another machine shop. I walked over to the Plaintiff, showed him the drawings, and asked if he could do the job. He hemmed and hawed a bit, and said "Sure". I left him the drawings, and he said he would come back with a quote.

He did so, and I came back, and, with some déjà vu trepidation, left him the parts to be modified. Well, this time it came out OK. He had them done when he said he would, and I picked them up. He even praised the quality of my manufacturing drawings, and asked if I might want to do some freelance drafting for him when the need arose. I said sure. It'll be fun to work with CAD again. I assembled the parts, and mounted them on the stove intake pipe. (Well there were actually more complications, but to enumerate them might convey my ever increasing sense if trepidation and frustration, but would just prolong the story with no benefit to the reader.)

So this is what it looks like in its final configuration. I filed a lead-in chamfer (ramp) on the edge of the aluminum plate, so as it rotates above the spring plunger, the plunger catches the ramp, and pushes the plate up against the lower surface of the valve body, closing the gap. Just in time. It dropped below 40° last night for the first time since summer, and I lit my first fire of the season. It definitely allows less air into the firebox, and the wood burns more slowly. It worked.

Ain't engineering fun?

August 22, 2019

Flying

Click on any image for a full screen view.

From the time I was in junior high school throughout my early years in college, I was a model airplane enthusiast. These were flying models, not radio control, but "control line". (Planes you fly around yourself connected and controlled by steel wires between the aircraft and a handle held by the pilot.). This pursuit occupied the bulk of my free time. I belonged to a model flying club, and flew for sport and competition, attending several national meets in Willow Grove, PA and Chicago, IL. Consequently I became an aircraft enthusiast, a condition that long outlasted my preoccupation with models. I've had several opportunities over the years to go up in private planes, and even sailplanes, and occasionally took the controls for brief periods of time. My interest in aviation persists today

In 2014, I was contacted by a fellow living near Detroit named Stephen Tupper. He is an aircraft uber-enthusiast. A lawyer by profession, he is a licensed aerobatic pilot and flight instructor, a Director of the Tuskegee Airman's Museum, the Director of the Detroit Air Show, has wrangled rides in F-16 Falcons with the US Air Force's Thunderbirds Aerial Demonstration Team, runs an aviation blog and podcast called Airspeed, and is in all respects a thorough aircraft nut. His relationship with aviation is akin to my relationship with folk music: a professional in all aspects short of making his living from it. (How he came across me is an interesting story unto itself, but not essential to this narrative. But if you're interested, here's the story.) So he came to see my show when I played Mama's Coffeehouse in Bloomfield Hills, MI, and we hit it off big. We had stayed in touch, and when I came back to play Mama's again in November of 2018, he offered to ferry me to and from the airport, put me up for the night, and take me flying the following day. Well, twist my arm!

November 19, 2018: Flight Aborted

My flight home was at half past noon on Sunday, so we had a very narrow window to get any flying in. So we were up early and off to Detroit City Airport. (A.K.A Coleman A. Young Municipal Airport, but everyone calls it Detroit City. See Photo 02) That's a rare bird of an airport, inasmuch as it's a "general" (i.e., private plane) airfield within the city limits of a major metropolis with no commercial scheduled flights. It looks to have been built in the 20s. It is showing its age these days, but still functional. The field is surrounded by an 8 foot chain link fence topped with razor wire to forestall vandalism to some valuable (and in some cases irreplaceable) aircraft, and entered through an electrically operated gate operated by an electronic pass card. We drove round to one of the big sliding hangar doors, and entered through a small person-sized door in one of the sliding panels. And there was our craft awaiting us, along with two more identical brethren. (Sistern?)

The Schweizer TG-7A (Photos 03 and 04) is a most unusual plane, as one might guess from its odd proportions. The wings are very long (59.5 feet) and skinny, like those of a glider. And in fact, that's what she is. She is a motorized version of the SGM 2-37, a sport glider built by Schweizer in Germany. The Air Force commissioned 12 of them in the 80s to serve as training planes for glider pilots. The idea was that it was more efficient to have the instructor and student take the craft up under its own power, and then shut down the engine for flight training, rather than needing to have a second plane and pilot tow it up to altitude. The planes were decommissioned sometime in the 90s, and three were donated to the Tuskegee Airmen Museum in Detroit, of which Steve is a Board Member. (For those unaware, the Tuskegee Airman, was a squadron of African American fighter pilots who defied the Army's opinion during World War II that Blacks were incapable of combat flying. They distinguished themselves with a sterling record of protecting American bombers from German air attacks over Europe.) For further information on the TG-7A, see this entry in Steve's "Airspeed" Blog.

The prospects weren't good for a flight that morning. It was spitting rain on the drive to the airport, and the visibility was iffy. Nonetheless, we (well...Steve) prepped the aircraft for flight. He powered open the hangar doors, and we pushed the plane out onto the taxiway. It was quite easy to push, but needed two people pushing at the wingtips to make sure we didn't bump into anything. But in the end, the clouds dropped to ground level, and visibility was reduced to a few hundred yards (See Photo 05). Steve, much to both of our regret pulled the plug on our expedition, with a promise of a rain check sometime in the summer when chances were better for weather more conducive to flying.

Treasures of the Hangar

* If anybody can provide more information on these unknown aircraft, please contact me.

** Thanks to John Gerty for the identification.

We reluctantly put the motor-glider back in the hangar. Having some time to kill before getting me to my flight home, Steve showed me around the adjacent hanger, which housed a treasure-trove of assorted strange and wondrous aircraft. It serves as a storage space for aircraft belonging to the Tuskegee Airman's Museum, the World Heritage Air Museum, and some private individuals. There were some that I recognized, like the Texan and the Stearman, but not a one was what might be considered ordinary. Steve says,

Many of the aircraft on the other side of the building are owned by the World Heritage Air Museum (“WHAM”), a museum dedicated to preserving and flying Cold War jet trainers. The museum's operation have come to a near halt after the death of Marty Tibbitts, the president, who crashed the Venom near Sheboygan, Wisconsin in 2018 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jmvMDKzytbM). I believe that the Tuskegee museum will receive one or more airframes and/or engines to use in teaching kids to wrench on jets. In the meantime, I don’t know what the plans are for the WHAM operations or aircraft.

Here's what Steve knows about the aircraft. If any of you readers can shed some light on the unknowns, please let me know.

Photos 11 & 12: AT-6G (sometimes known as the “Texan” and, if manufactured by the Canadians, the “Harvard”) flown by the original Tuskegee Airmen. It’s an advanced trainer that candidates flew after their primary training usually in the PT-17 and before their tactical assignment in operational fighters, P-47, P-51, etc. Owned by the Tuskegee Airmen National Historical Museum.

Photo 13: Stearman PT-17. A primary trainer. This aircraft is what turned pedestrians into pilots during WWII. This is a fully aerobatic craft, either as manufactured, or retrofitted with more powerful engines and other enhancements. If it would be ready when I came back to Detroit in summer, I hoped to get a ride in it, and have Steve turn me upside down. This aircraft is owned by the Tuskegee Airmen National Historical Museum and is undergoing engine maintenance and a complete avionics overhaul.

Photo 14: Fouga-Magister CM-170 An advanced jet trainer built in France, and owned by the World Heritage Air Museum. Note the V-tail.

Photo 15: According to Blog reader John Gerty, this is a Zeff Aaron Murphy Moose, an experimental amphibian that last flew in 2012. .

Photo 16: Hispano Aviacion HA200 owned by the World Heritage Air Museum. The HA200 Saeta (Arrow), Spain's first turbojet powered aircraft, was an advanced jet trainer designed by Willy Messerschmitt for the Spanish Airforce in the mid 1950s.

Photo 17: Sea Star Turbo. A really cool-looking amphibian.

Photo 18: Anoter Saeta. According to John Gerty, "...almost the same thing as ... #16 Hispano Aviacion HA200 Saeta. There was an upgrade to these jets, the HA-220 Super Saetas. There was a variant, the Ha-200Bs license-built in Egypt as the “Al-Kahira“. The desert camo made me think of this, but the red/yellow roundel markings are clearly of the Spanish air Force."

Photos 19 & 20: Unknown Russian plane. My guess is that it's some kind of jet trainer, along with others from the World Heritage Air Museum. Apparently the entire airframe aft of the cockpit is removeable in order to service the engine. Very clever. According to John Gerty, "The tailpipe opening looks like a Mig 15. I can't find a picture of a Mig 15 with a dorsal section running along the top of the fuselage. Also the speed brakes are not in what seems like a typical configuration from the Mig-15 photos I can find online. The engine is clearly one of the older style turbo jet engines. However, the twist to the combustion chambers are not typical to the Mig 15 engines I can find online."

Photo 21: Aero Vodochody L-39 Albatros owned by the World Heritage Air Museum. A high-performance jet trainer aircraft developed in Czechoslovakia.

We packed it in, and Steve got me to the (other) airport in plenty of time for my flight home with promises of a return visit sometime in the summer for some air time.

August 22, 2019: This time for real!

Sometime this past February I had scored a couple of gigs in the Minneapolis area. And when I looked at the map, I saw that Detroit was conveniently placed en route between there and New Jersey. So I called up Steve, and asked if I could stop by on the way home, and take him up on the rain check (fog check?) he had offered. He was fine with that, so we scheduled a 3-day visit. I was lucky enough to find a great bargain on the 3-leg flight for $350 total (not including checked baggage). We'd go flying on Sunday the 22nd, and check out some other tourist attractions in the area on Monday and Tuesday. ("Tourist attractions in Detroit??" you scoff. Don't knock it. The Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village are pretty spectacular. Steve and I, both being techies by nature, also opted for a tour of the Ford final Assembly Plant in Willow Run. And for those of you who are more into more conventional tourist fare, the Detroit Institute of Art has a great rep. But our extra-curricular activities are not the subject of this Blog post. Close parentheses)

Alas, the Stearman was still not airworthy, so that will have to wait for another day. But the TG-7A is nothing to sneeze at. At a glance, it's obvious that this is no everyday Cessna. The long narrow wings suggest the glider upon which it is based, but there's that propeller in front that clearly refutes that impression. And then there is the World War II military paint scheme of school-bus yellow (indicating a military training plane) and the "Star and Bar" insignia on the wings. And our flight plan was pretty cool, too. The plane is one of three identical craft that belong to the Tuskegee Airman's Museum (Photo 31). Steve and I were to go up in one of them, and Steve's son FOD (Photo 30) was to take the other, and we were going to tool around over Detroit in formation.

FOD's given name is Nicholas, but everyone knows him by his aeronautical handle, which stands for "Foreign Object Damage". The term applies to the damage to jet engines that can occur while taking off, landing, or taxiing, from ingesting any of the assorted litter that might accumulate on a runway. His dad gave him that nickname because as a toddler, he'd leave his toys scattered all over the floor and stairs. FOD was indoctrinated early into his dad's aeronautical ways, and accepted that indoctrination happily. He learned to fly before he could drive. And today at age 17, he's well on his way to an instructor's license. It must be really cool as a high school kid to tell your buddies, "Sorry, I can't make it next Saturday. I'm flying in the Detroit Air Show." And let me tell you after having gotten to meet him and talk to him at length, irrespective of all that, or maybe even because of it, FOD really is a cool kid.

We arrived at the airport nice and early. I followed FOD through his pre-flight check of the plane he'd fly, while Steve pre-flighted our ship. He carefully inspected the tires, the freedom of motion of the control surfaces, the engine oil level, the pitot tube (that senses the airspeed), and various other external parts of the plane. Considering that gets done for every flight, it makes me wonder how much we're taking for granted every time we just get in the car and drive off. I guess the chances of something going wrong are just as small, but the consequences are a whole lot bigger. We pushed the two planes out of the hangar and onto the taxiway (Photo 32). Topped off the fuel tanks, and I climbed in with Steve.

I strapped in. The 5-point harness held me firmly in my seat by restraints across my lap and both shoulders. Unlike most training planes, the student sits in the left seat of the TG-7A. Steve manipulated stick, rudder pedal, and dive brake handle, while we visually observed the movement of the control surfaces (Photo 33. The graveyard on the far side of the airport fence gave me pause for a few moments.) We started our engines and headed out to the runway (Photo 34). Taxiing a "tail-dragger" is clumsy, because the nose of the plane obscures one's view of what's in front of the plane. At the head of the runway (Photo 35), even though he has done this probably a thousand times before, Steve still went through the pre-flight checklist out loud, item by item, actually checking each item off against a written list. Caution is a ritual with pilots. Almost a religion. And then, throttle to the firewall, we accelerated down the runway, and we were off (Photo 36).

FOD was right behind us, although we did not actually take off in formation as might be done in an air show. We leveled off around 2,800 feet, well below the commercial traffic. We flew around with no particular destination in mind, but mostly as practice exercise in formation flying. For a while Steve flew lead with FOD in trail (Photo 37), and then in response to a signal from Steve, FOD moved up to the lead (Photo 38). It's interesting to watch another plane fly that close. Something you don't usually encounter in normal air travel. It didn't seem scary or anything; just something new and different. We were about 20 minutes into this exercise, making turns and changing altitude while concentrating on maintaining position relative to one another, when FOD reported an anomalous reading in his fuel pressure gauge. (When was the last time you even looked at any of the engine instruments in your car? Like I said: caution is almost a religion with pilots.) We determined that FOD would go back to the airport and land, while Steve would give me some flight instruction.

Steve followed FOD back to the airport and hung back, following him while he went through his landing pattern (Photo 39) and touched down (Photo 40). (Another perspective one doesn't normally get when flying commercial: watching a landing from above.) You shoulda seen him beaming as his kid greased the landing perfectly! When the runway was clear, Steve did a "touch-and-go", a landing and immediate take-off without coming to a stop.

Then it was my turn. (No photos for this portion of the flight for obvious reasons.) I had had some stick time in the past, both on powered planes and gliders, but never any concentrated instruction. Steve coached me on the basics -- just getting the airplane where I wanted it to go. It's not like a car. You use the stick and rudder to initiate a turn. But then you bring the controls back to center to continue the turn. If you keep the stick off-center the way you would with a car's steering wheel, the turn will keep getting steeper and steeper until you are in a spin. When you want to straighten out of the turn on a new heading, you need to give opposite control to straighten out. So I practiced making 360° turns, trying to maintain the same airspeed and altitude throughout the maneuver, and not side-slipping one way or the other, and straightening out on the same heading I started from. More complicated than one would suppose. There are more factors to keep track of than with a car. And I was still trying to familiarize myself with the layout of the control panel. "Oh drat! Where's that altimeter? Who stole the altimeter?" And meanwhile while I was looking for that, I'd let my airspeed drop uncomfortably close to where the plane would stall (not fly fast enough to provide enough lift to keep flying). And all the while I knew I needed to keep my eyes peeled for other air traffic in my vicinity. I felt like the first time I'd played a "first-person shooter" video game, and still trying to figure out how to walk while the bad guys started shooting at me.

It wasn't really scary. Just a little frustrating. I knew that when I had enough flight time under my belt, I'd be able to internalize my responses to visual and tactile input, and make the appropriate corrections without thinking about them. I just wasn't there yet. Not by a long shot. Flying around the Lake St. Claire shore (Photo 41) was very helpful. It very quickly oriented me as to which way I was heading. We had picked a great day for flying with almost unlimited visibility. After a while I felt more comfortable, and ventured doing figure-8s and S-turns and the like. At one point, Steve pulled the throttle down to idle, and said, "OK, you've just lost your engine." And I did exactly the right thing; I put the nose down a little to maintain airspeed, and just kept flying. This was, after all, a motor-glider, and designed to fly without power. Cutting the engine would have had considerably more effect on a more conventional aircraft.

After about an hour, we figured we had had enough fun for one day, and headed back to the airport. Steve had originally wanted to shut down the engine, and land "dead-stick" in glider mode. But there was a pretty brisk cross-wind. And Steve opted for a power-on landing. Once again, caution takes precedence over fun.

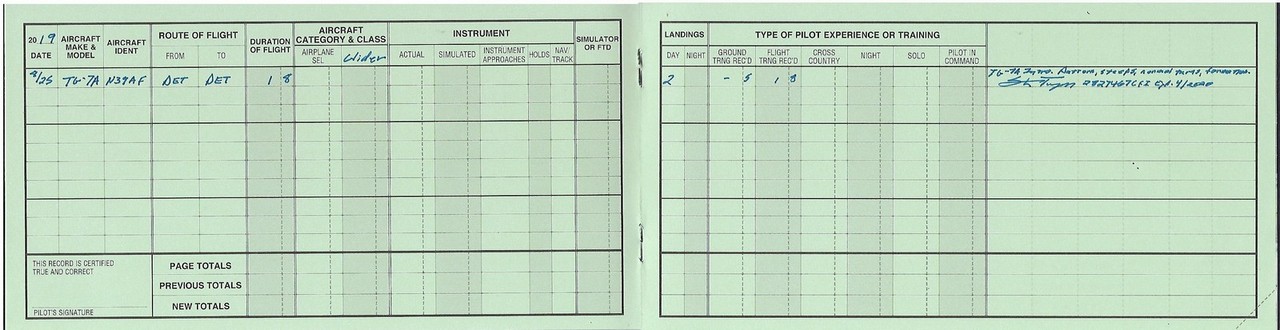

Well, that was fun. And I now have an official log book (Photo 44) crediting me with 1.8 hours of flight instruction. Can't wait until the next time. Maybe I'll get that ride upside down in the Stearman.

July 29, 2019

Bye-Bye Mini 3

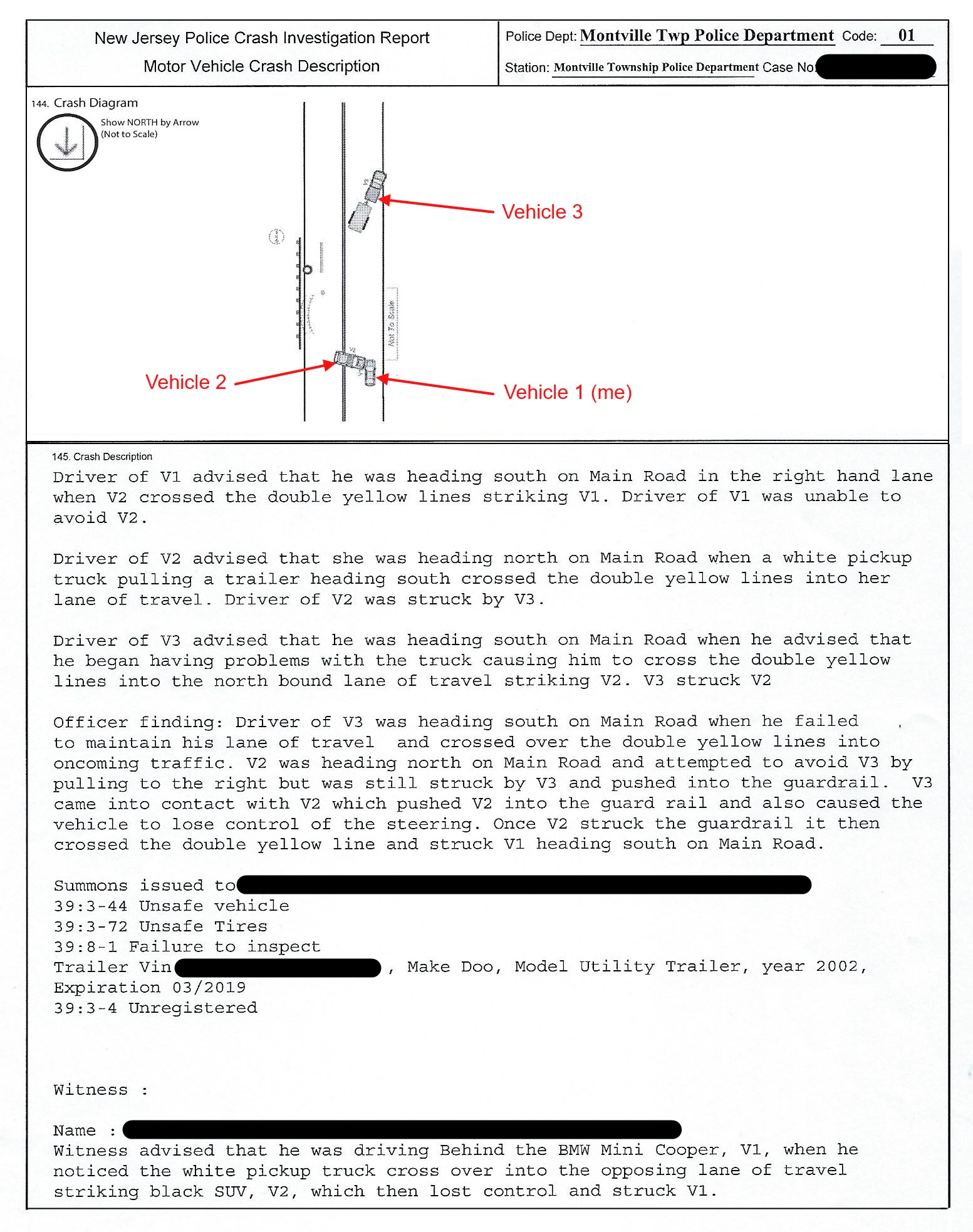

Coming home from visiting Jenny in Vermont on Monday afternoon, I was involved in an auto accident. And for once, it wasn't my fault!! I have proof. Here;s the police accident report.

I think that pretty much tells the story. One minute I'm 5 miles from home on the last leg of a 250 mile trip, and the next I'm sitting in the driver's seat looking through a cracked windshield with no glasses, and the smoking remains of several flaccid air bags about me. I looked around me, and my neck really hurt when I rotated it just a bit. Other than that, nothing hurt. People called out to me, "Are you OK?". And I replied, "I don't know." I might have been unconscious for a few minutes. I don't remember the emergency vehicles arriving, but they were all around.

The EMTs got me out of the car, and onto a gurney, and into an ambulance. I was mildly dazed, but mostly lucid for the whole process. Talking to the medic in the ambulance, I realized I didn't have my hearing aids in my ears. I asked if they had removed them, or retrieved my glasses from the car, and they said no. Both must have been dislodged from my head from the impact of the airbag. I did insist that my phone, guitar and concertina come with me to the hospital. Other than the stiffness and pain in my neck and upper back, and a minor scrape on my right wrist I appeared to have no other injuries. I had been traveling at a moderate 30 - 35 MPH at the time of impact. The police gave me a card with the name and phone number of the towing service that took my car away.

In the hospital, I called my friend Mark Schaffer, and asked him to be ready to take me home if I was released. In relatively short order, the ER doctors sent me to have an MRI taken. The results showed no broken bones or other internal injuries. They sent me home within 2 hours of my arrival, with instructions to take Advil for the pain in my back and neck. The air bags really worked as they should. My instruments were also uninjured

I spent an uncomfortable night, but I did sleep. The next day my friend Chris Riemer picked me up and took me to the yard to retrieve my belongings from the car. He also took the photo above. There was little doubt that the car was totaled. I scoured the interior, and found my glasses and one hearing aid. I assume the other had landed in my lap or on the driver's seat, and was swept into the road unnoticed when the EMTs got me out of the car. That'll be partially covered by my insurance. (Speaking of insurance, I have nothing but the highest of praise for Amica Insurance Company. They are a smaller national company based in Providence, RI. Great service, low premiums, no hassles, and fair payouts. They don't advertise, and use the money saved to keep prices low, and let their clients do their advertising for them.) Chris took me from the towing yard to a car rental company, where I picked up a car to use in the interim. I then stopped off at the audiologist to order a replacement hearing aid, which I picked up on Friday.

Over the next two days, the stiffness and pain in my back and neck, and ribs increased, but started to subside on Friday. I decided to skip the Falcon Ridge Folk Festival this weekend. While the discomfort continues to subside, I don't think I'm ready to spend the night in a tent on the ground just yet. Thursday, I went down to the Mini dealership planning on ordering a replacement for the old car. But I discovered to dismay that as of 2020, they are discontinuing manual transmissions. They are abandoning their sporting base, and concentrating on bigger 4-door models. John Cooper is twirling in his grave. If I were in my grave, I'd be twirling too. They found a new 2019 that I will probably buy, but it's the wrong color, and not equipped exactly as I would like it. I'll accept the changes in equipment with grumbles, and I may have the damn thing painted before I take it home. It will obviously be the last Mini I will buy. I'll finish this report up with a post script when I get the new car. Meanwhile, if anyone knows of a green and white Mini Cooper 2-door hardtop (Not the "S" model) with manual transmission, navigation, heated seats, and LED headlamps, 2017 or later, who might want to trade it for a new 2019 model, have them get in touch with me.

Postscript: September 20:

Hello Mini 4

New car came in last Friday. I did get it painted, a totally unjustifiable expense. But I knew that every time I'd get into the car, it was gonna bug me. "This isn't my car. My car is green." So I splurged for it. Other differences from Mini 3:

- The wheels are black instead of silver.

- It has a sun roof. (I had declined getting the sun roof on #3 as being not something I really wanted. But I find that I like it.

- It doesn't have Mini 3's high-intensity headlamps. I am really going to miss them. The high beams illuminated the road all the way to the next zip code, and the low beam pattern was spectacular: extremely brilliant up to the level of the bottom of the rear window of the car in front of me, and then absolutely black above that, with a sharp border that looked like it was done with masking tape. And unfortunately they were not retrofitable. Because of the potential for the low beams to blind oncoming drivers if I put a heavy load in the back, their aim was self-adjusting. They came equipped with a sensor on the rear suspension, which would detect if such a load depressed the rear springs, and would automatically tilt the headlights back down by means of a servomotor, so as to aim parallel with the road surface. So installing the high-intensity lights also would have also required installing the sensor, the wiring harness for the sensor, and a new computer to control the aiming of the headlights. That would have come to something over 10 grand, and I really couldn't justify that. I will buy aftermarket LED bulbs for the headlights, though.

- The audio/navigation system is improved. The old one used to be very fiddley in connecting to my phone via bluetooth. And the map display is improved, and now utilizes traffic density information to suggest alternate routes with much greater reliability and clarity of instruction than in the old car.

- Gas mileage is a bit worse than the old one. I had been averaging about 37MPG on the old one, and thus far, only 33 on the new one. But the new one is probably still breaking in, and I'm dealing with a very small sample of only two fill ups since I got it. So that may improve.

- Oh, yes. And the front left fender and engine compartment of the new one isn't all smashed in. That's different, too.

Yes, on the whole, the new car is somewhat of an improvement on the old. But all things considered, I would have rather have not had the accident, and still be driving the old one.

June 26, 2019

Still Life with Flowers, Flag, and Fungi

Just a random bit of beauty I encountered Monday on my morning run. Worthwhile to stop and snap a pic. Caught it just in time. The homeowner didn't appreciate the fungi, and removed it the next day.

Postscript: July 2, 2019

I spoke too soon. The fungi are still there. I had just been looking at a different stump with flowers on top at the other end of the property.

Never mind.

April 27, 2019

Springtime in New York

Springtime in New York! Somehow doesn't have quite the same cache as Springtime in Paris. But New York City is a real place, and Spring can put a lovely face on even the most mercantile of cities. I was born and bred in that big Briar Patch, Brer Fox. I grew up in Inwood, close to the northern tip of Manhattan, and looked up out of my bedroom window at the tower of the Cloisters atop Fort Tryon Park. I'm happy to be out of the City now. Too crowded. Too noisy. Way too expensive. But I'm not intimidated by the place, and will make the trip in when the occasion warrants.

This occasion was to be a tourist in the city of my birth, and see some of the newer sights down at the bottom of Manhattan. Back in November, I had been contra dancing down in Greenwich Village with my friend Abby, and she had told me about the Oculus. And I had been hearing wonderful things about the High Line, which was in the same general area, and which Abby likes too. So I had asked her to show me around those two attractions when the weather got warm again. And lo! It's springtime in New York. Let's go.

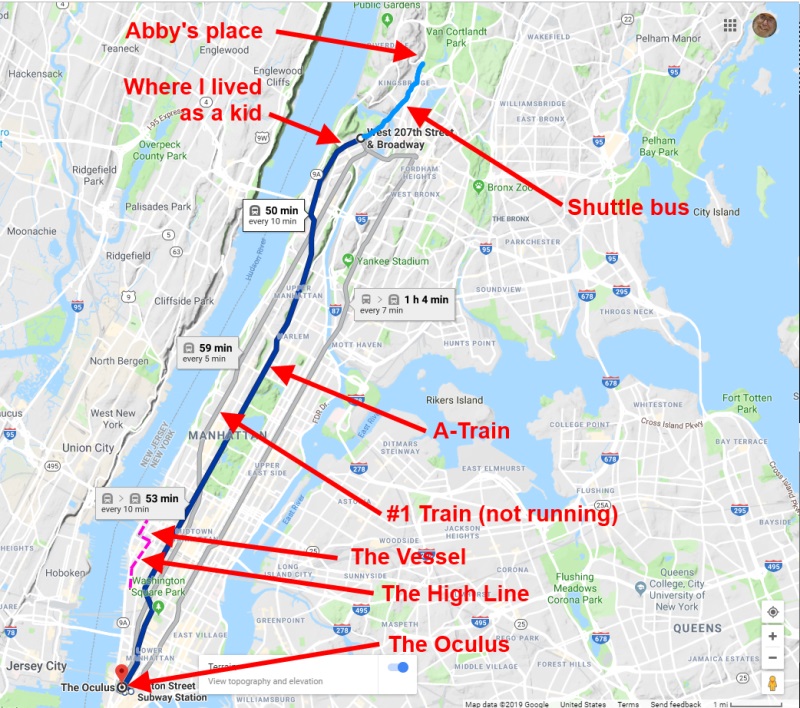

Abby lives in the Bronx in Riverdale. When we had gone dancing in November, I made the mistake of picking her up and driving down to the dance in Greenwich Village. The traffic these days is much worse than it was when I was younger, and I had underestimated how bad it would be on a weekend. So this time I parked up by Abby's, and we took the subway downtown. She lives near the 242nd Street station of the #1 Train, which is elevated above the street at that point of the line. 242nd St. is the last stop on the line, right by Van Cortlandt Park. As a kid, I used to take the #1 to that station to work my Saturday job as a sales clerk at Brown's Hobby Center, right across the street from the park. So it was familiar territory.

But when I arrived, Abby told me that the #1 was shut down for repairs all weekend. But the MTA (Metropolitan Transit Authority) had arranged for free shuttle busses to run along the route of the #1 into Manhattan, and then divert a few blocks westward to let riders pick up the A Train at 207th Street, which ran parallel to the #1. That was kind of nostalgic for me. I had lived at home while I was at college, and I took that A-Train to school in Brooklyn every day. The trip down went fine; we took the bus to the A, and rode the A down to the Fulton Street Station, and walked to the Oculus. It would not go so smoothly on the way home.

The Oculus

The Oculus is essentially a 3-1/2 billion dollar high-end shopping center built as part of the reconstruction of the area that was destroyed by the sabotage of the World Trade Towers during the 911 attack. I'm assuming that it got its name from the resemblance of the structure when viewed from the side to a human eye wearing long false eyelashes (Photo 1) With the exception of a very large Apple store and a Dunkin Donuts, there is very little in any of the shops that interests me in the slightest. But I am fascinated by the architecture. The structure is primarily of tubular steel bent into pleasing free-form shapes and welded. In many places it resembles the skeleton of some huge beast as seen from the inside (Photo 9). Some internal support columns are also multi-tubular concoctions, rather than a simpler single support (Photo 2)*.

The building also serves as a major transit hub, connecting 11 different subway lines (Photo 8) and the PATH (Port Authority Trans-Hudson) commuter train lines (Photo 9) The building has some aspects of a cathedral (Photo 5), and in some places, those of the great wrought-iron train sheds of late 19th Century railroad terminals (Photos 3 & 6)*. The main hall has an observation platform (Photo 4) at both ends, affording dramatic views of the main hall (Photo 5). I was particularly impressed and surprised at how noisy that hall wasn't. One would expect that with the huge high ceiling and hard terrazzo floors, the place would have echoed like a cathedral. But it didn't. I guess all of those tubes break up the reflections of the sound waves.

* Abby, on reviewing this account tells me that photos 2, 3, and 6 were not taken in the Oculus, but in an adjoining structure called Brookfield. (An odd name for a place so far removed from any brook or field.) But it's an interesting looking structure, anyway.

As I write this some 2-1/2 weeks after my visit, I hear on the news that the skylight over the main hall is leaking and has been temporarily sealed up with tens of thousands of dollars worth of what is essentially high-strength duct tape. The irony of that is not lost on me.

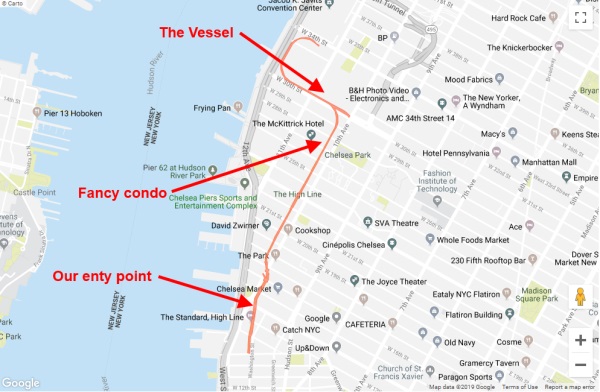

We wandered around the Oculus for about an hour or so, and then took the subway uptown a couple of stops to 14th Street, and walked a few blocks west to the High Line. As we walked, it became apparent that it was indeed Springtime in New York. The few instances of actual earth poking through the pavement had been planted, I assume by local residents, with flower beds (Photos 10 & 11 below), providing a cheery splash of color. [According to one Blog reader, those flower beds are actually planted by the Parks Department.] And as we approached 10th Avenue, I could see the elevated structure of the High Line, and the stairway that led up to it.

The High Line

According to their website,

"The High Line is a public park built on a 1.45-mile-long elevated rail structure running from Gansevoort St. to 34th St. on Manhattan’s West Side. The High Line was founded by neighborhood residents in 1999 to prevent the elevated rail track from being demolished. With the close partnership of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, the High Line has transformed into a public space where every New Yorker and visitor is welcome and can experience the intersection of nature, art, and design. The High Line also facilitates a national learning community, called the High Line Network, for leaders of similar projects."

Although I live in New Jersey, I get most of my news from WNYC, New York City's public radio station. And ever since its opening in 2009, there had been a lot of local press about the High Line, almost all of it high praise. So I had been curious to see it. And I had visions of an oasis of sylvan tranquility in the midst of the bustling City. In this, I was sorely disappointed. First of all, the thing was built, after all, on top of an elevated railroad structure. So it was only 30 feet or so wide, which doesn't leave a lot of space for expansive vistas of greenery. And what few trees were planted on it were of necessity pretty small, as there wasn't much depth of soil available for a root structure. Then, since the park opened, Hudson Yards, an enormous development of high-end high-rise condos, offices, hotels, and stores had sprung up around the structure, hemming it in, and cutting off any vistas of the Hudson River except at its northern-most end where the structure veered west to the river. On top of that, it was noisy. There was the constant din of horns, sirens, diesel exhaust, and the general cacophony of New York City. And what greenery was there was only for looking at, not walking on. It would have never survived if people were not restricted to the paved path that meandered along it's narrow surface, as a result constricting all the foot traffic to a 10-foot wide corridor. It didn't help that this was the first really nice spring weekend day of the year, and the mobs were out in force. So making any progress was no walk in the park, if you'll forgive the expression. Photo 12 will give you the general idea.

In some places they left sections of the old rails amidst the greenery to remind you of the structure's original purpose. (Photo 13. Actually they probably just rebuilt the structure, and then laid new sections of rail upon it.) Looking westwards along 26th Street (Photo 14) shows a tiny slice of the Hudson River between the canyons of the buildings. On certain days of the year the sun will set right on the center line of the street, giving the phenomenon the nickname "Manhattan-Henge". Photo 15 shows a rather snazzy luxury condominium that went up as part of Hudson Yards. I wonder how the owners of the 3rd floor apartment like having the mobs looking into their windows from around 15 feet away. As the path swung west to follow 30th Street, we caught our first glimpse of what I felt to be the highlight of the walk: The Vessel (Photo 16).

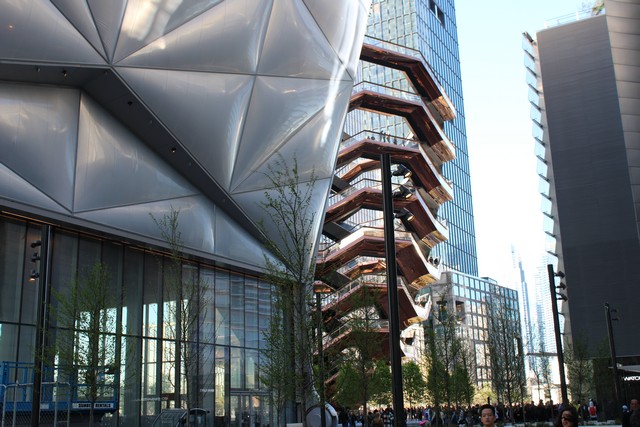

The Vessel

I had not known about the Vessel until I encountered it on this walk. It was commissioned by Hudson Yards as a piece of artwork that could be visited. There's an elevator that will take you to the top if you don't want to climb the myriad staircases. Admission is free, but there are a limited number of tickets that one needs to reserve ahead of time. (They probably need to prevent overloading the structure as well as overcrowding it.) The fact that they must have spent an enormous amount of money on it, and devoted a huge plot of potentially income-producing New York City real estate to it says something good about somebody. The photos do not really reveal the structure. In fact, looking at it in person doesn't really reveal the structure. It is quite beautiful. And from an engineering standpoint, I marvel at a number of things about it. The outside surfaces appear to be clad in copper. But how do they prevent the surface from oxidizing to that familiar green patina like the Statue of Liberty? (Did you know that it is fashioned from sheet copper too?) And never mind that patina; how do they keep it so clean and shiny in grimy New York? And for that matter, how did they manufacture the mirror smooth and polished compound curved shapes of the pieces in the first place? All mysteries to me.

Needless to say, we did not obtain tickets. They had probably been scarfed up days or weeks ago. But we enjoyed looking at it from all angles on the ground, and watching the people.

By now we were getting hungry, so we found the nearby Stardust Diner, a real old-fashioned Art-Deco diner straight out of the 30s. We then took the subway back downtown again to 14th Street, and walked thence to the Church of the Village on 13th Street for the New York Country Dance Society's weekly contra dance. It turned out to be a great dance, with Pete Sutherland providing the music along with about 30 teenage kids from Vermont whom he'd been mentoring on playing fiddle tunes.

As good as the dancing was, Abby wanted to leave at halftime, having something to do early next morning. I had been on my feet all day, and dancing for half the evening, so I was willing to call it a night too. We picked up the A-Train uptown, expecting to retrace our steps to her home. And sure enough, over the loudspeakers on the train came the announcement about no #1 Train service over the weekend, and the availability of the shuttle bus to provide access to the #1 Train stops north of 207th Street to the end of the #1 line. But when we got to 207th Street we came out of the station to find a small mob of people waiting for the shuttle bus. From the conversations, we found that some of them had been waiting a long time.

We hung around for about 15 minutes, and still no shuttle showed. I started looking for taxis, but Abby finally said, "Let's walk." That didn't surprise me. I've gone walking with her before. She's only 5' tall, but she can walk me into the ground. I was pretty pooped, and it was a good 2 mile hike. But I said OK. We started out, with me occasionally looking back over my shoulder for a shuttle bus or a taxi. After about 1/2 mile, we came under the elevated tracks of the #1 Train along Broadway. And maybe a half mile later, I heard the rumble of a train on the tracks behind me. As it passed overhead, it suddenly dawned on me: Hey! I thought the #1 was not in service over the weekend! No wonder there was no shuttle bus. The damn train was running! They just neglected inform anybody about it. Including the lady who gave the announcement over the loudspeakers on the A-Train. When we finally got to Abby's place, she checked the MTA website, and it still said that there would be no #1 service until 5:00AM Monday. Curse you, MTA!!

Oh, well. We still had a lovely day. I said good night and drove back home, getting in at 2:00AM. Needless to say, I slept in Sunday morning..

March 31 - April 4, 2019

St. John

I had suggested to Jenny that we get away from the doldrums of winter and mud season and go someplace with beaches and palm trees and the like. She agreed, and we set up our usual division of labor: She'd do all the planning, and I'd do all the driving. Alas, when we compared schedules, the first time we could both get away at the same time was March 31 through April 4, a week after the cold weather had finally broke. Oh well. We can suffer through that.

It was to be a short trip this time; only 5 days. Jenny had introduced me to the Caribbean about 25 years ago, and we've made vacations to several islands since. She chose St. John in the US Virgin Islands, a place we'd not been before.

Click here to enter the travelogue.

March 19, 2019

Adventures in Technology

Monday, around 2:00 AM I awoke to a cold house. Well, colder than it should have been. Around 60°. Nothing life-threatening. But definitely indicative of something wrong. I got out of bed and felt the heat register. Cold.

Now I am well familiar with my heating system. In fact, I've fiddled with it and made so many alterations and improvements and Rube Goldberg additions to the system that if I ever sell this house, I'd have to include a service contract in the deal. As originally built in the 40s, the house was a summer cabin. When I first moved in, the house had been "winterized" by previous owners with minimal insulation and an oil-fired boiler feeding a baseboard hot-water heating system. That was able to heat the house to maybe 60° above the outside temperature. Which was OK except for the very coldest days of the year, when it would get downright chilly.

The living room had a fireplace (See the last photo of my Jan. 2 Blog entry below.) into which I had installed a wood-burning stove insert soon after I first moved in. The stove was one of those double-wall dealies that had blower attachment to blow air into the bottom of the chamber between the two walls, which would be heated by the fire, and expelled at the top of the chamber. That was rather noisy, and didn't really circulate the heated air very far into the house. So I took the next step..

I removed the blower, and replaced it with a steel manifold I designed and had manufactured which opened into the double wall chamber where the blower used to be, and also opened straight downwards. I broke through the hearth stone below that opening and through floor into the garage below. Then, with conventional household ventilation ducting, I ran a duct just below the garage ceiling to an intake at the very back of the living room. And in that duct, I installed a small conventional house ventilation blower. So now the blower takes the cold air from the back of the living room, and blows it into the heating chamber around the stove and out into the front of the living room. And since cold air is being sucked out of the house into the intake at the back, the warm air migrates through the room to replace the cold air.

Worked like a charm. The stove is able to keep the living room 80° above the outside temperature if I run it flat out. So the first sub-zero night that first winter with the stove, I was warm and comfy and satisfied with my handiwork. Unfortunately, the thermostat for the main heating system was also satisfied, and felt no need to run the baseboard heaters. Which were situated along the outside walls of the house. With just 3-/12 inches of fiberglass insulation between them and the sub-zero outside. You engineers out there can see it coming. The water in the heating registers froze. Which meant that when the fire died down, and the living room got down to the setpoint of the thermostat, the circulator pump couldn't move the heated water through the system due to the ice blockage. And the pipes got colder, and colder, and colder, until at 2:30 AM I was awakened by the first GUNNG! of a burst pipe. Over the next three days, I had every pipe in that heating system in my hands at one time or another in a 10° garage fixing split pipes and burst joints. Something needed to be done about this.

So here's what I did. I plumbed in a bypass pipe in the heating circuit that would allow the water to circulate, but bypassing the boiler, so it would not take any heat out of the boiler. I also installed an electric diverter valve on that bypass, so I could choose to run the water through the bypass or through the boiler, depending on which way the valve was open. And then with some spare parts from the lab at work, and using 1950s relay technology, I rigged up a little control box with two buttons on it, one labeled "Boiler", and the other labeled "Stove". And here's what they did: I'd light a fire in the woodstove, and once it got going good, I'd hit the "Stove" button. And here's what it did:

1. Turned on the blower in the garage.

2. Threw the diverter valve to bypass the boiler.

3. Turned on the circulator pump in the baseboard heating system. Now the water would continue to circulate through the system, never standing still long enough against the cold outside walls to freeze.

4. (And this was the real clever part) It changed the function of the room thermostat. The new function of the thermostat was that when the fire in the stove died down, and the room temperature came down to the setpoint of the thermostat, it reversed the previous three actions: It turned off the blower, threw the diverter valve to send the water through the boiler instead of the bypass, and returned control of the circulator pump to the heater control box. And it also returned the thermostat itself back to its normal function of maintaining the room temperature at its setpoint.

It was the world's most hairbrained cockamamie Rube Goldberg kluge you could ever imagine. But it worked like a charm for 40 years, and cost me maybe 150 bucks in parts.

But Monday morning at 2:00 AM it had stopped working.

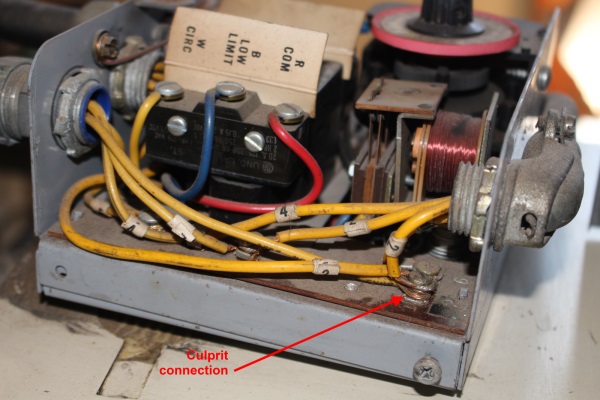

I got out of bed to investigate. First of all, the gauges on the furnace indicated that it was working properly. The temperature of the water in the furnace was 160° as it should have been. And the diverter valve was indeed set to route the water through the boiler. That meant the circulator pump wasn’t operating to move that hot water through the system. Putting an ear to the pump motor confirmed it was not turning. Something had gone wrong with my system.

I had thoroughly documented the system with schematics and diagrams, but so long ago that it was almost like starting over again. I had to back-engineer the system, and figure out what my original logic was when I created it. In order to trace where the failure was, I got out my volt meter to test step by step which points of the circuit were live and which were not in order to locate the failure. I was poking around with the meter probes, when suddenly a relay clicked, and the pump motor started up again. I didn’t see what I had done to cure the problem, and I couldn’t diagnose the problem because the problem had disappeared. I went back to bed.

Of course, in the wee hours of Tuesday morning I again awoke to a cold house. But armed with prior knowledge from the previous night, I knew where to take up the search. Out with the volt meter again. And as I touched the probe to one of the terminal screws in the furnace control box, I saw a tiny spark from the terminal. It was a ground terminal with three ground wires all secured under the one screw. And after 40 years, that screw had worked loose, and one of the wires had worked free. Ta-daaaaah! That’s what I must have poked at last night to restart the system. I must have jiggled the loose wire enough so that it made tenuous contact with the screw, and made the connection. But it was still loose enough to break the connection from vibration of the furnace, and failed again Tuesday morning.

I re-positioned the wayward wire under the screw, and tightened it up. Then I powered up the system again and put my hand on the pipe leading to the heating registers. Sure enough, it soon started to get hot, indicating that the hot water was indeed circulating. Fixed!!

It’s still a pretty iffy connection. I’m going to go out an buy a bunch of ring terminals to put on the ends of all those wires to assure a more secure connection for the next 40 years.

Ain't technology grand?

January 2, 2019

A Blast From the Past

One Saturday afternoon last August I was surprised by an unexpected knock on my door. Now, pretty much any knock on my door is unexpected, because nobody knocks on my door. If I'm expecting a visitor, I'll hear the crunch of gravel on my driveway, and step out to greet them. And if I'm not expecting a visitor, they can't find my house. Even if I give them the address. You can't see my house from the road, and my driveway is long, and overgrown, and inconspicuous, and people drive right past it. I don't even get any trick-or-treaters on Halloween.

But this particular visitor had good reason to be able to find my house. Seems that her family owned the place about 65 years ago. Standing on my deck was Sandy VanTilburg, along with her husband and cousin. They were visiting the area from their current Texas home, and on a whim, dropped by to see the old place where she used to spend her summers as a kid. Well, of course I invited them in to look around.

What a treat for all of us! Of course, the place had changed enormously since then. For one thing it used to be a summer cabin: uninsulated, unheated (except for a through-the-wall propane heater resembling a primitive air conditioner), and very rustic. And for another, back then the place was only one storey with a crawlspace. When I moved in in 1980, it was still only one storey, but the house had been marginally insulated, and plumbed with a baseboard hot water heating system, and an addition was tacked onto the side with a utility room with a boiler. The propane heater was still there, but non-functional. The back yard borders on the Rockaway River, which, unknown to me at the time I bought it, occasionally comes to visit. (See my Blog Entry of March 11, 2011, God Willin' an' the Crick Don't Rise.) The first time the house got flooded, I resolved to do something about it. Over the course of the next year, I had the house raised about 6-1/2 feet, and turned that crawlspace into a full under-house garage. (That whole story is probably worth another Blog entry sometime. Alas, I did not own a camera then, so there would be no pictures.)

So, of course I invited them all in, and showed them all the innovative things I did to the house to turn those periodic catastrophes into minor inconveniences. And they regaled me with tales of idyllic summers spent on the river when the world and all of us had been younger. The visit lasted an hour or more, and when they left, they promised to send me photos of the time. Those photos arrived last November, and I finally got around to writing up this blog entry.

Click on any photo for a full-screen view

|

|

|

|

|

Says Sandy concerning her tenure in the place:

My grandparents, Bessie and Nathan, owed the house. I am not sure what year they purchased it but I would think sometime in the late 1940's or early 1950's. I am not sure if it was new when purchased. The house was a summer cottage, with no heat for the winter. My grandparents lived in Brooklyn and had two children. My family lived in Queens and my uncle and aunt lived in Brooklyn. Originally the entire family would spend the whole summer at the cottage. At some point, the house was deemed to small for all of us, and for as long as I can remember, we split the summer months. My grandparents stayed all summer and my family would spend either July or August, with my cousins getting the other month. We rotated months every year - if we were there in July this year, the next year we would get August. Memorial Day went with July and Labor Day with August. I spent every summer there from the year I was born until the mid 1970's. It was the happiest time of the year for me. It was more than just being off from school. To me it seemed that we were all relaxed and relatively carefree there. I felt the cottage brought out the best in all of us.

The series of floods over the years with the ensuing evacuations, clean-ups, and furniture replacement, eventually wore down the grown-ups. My grandmother's health was worsening and the grand-kids were pursuing other teenage and early adult activities. The house was sold in the mid 1970's, but as you now know, it has always retained a very special place in my heart.